Examining Reasonable Doubt

- Austin Vidal

- Oct 5, 2023

- 5 min read

Without exception the most critical aspect of every American criminal trial is the standard of reasonable doubt. This standard is the bulwark that protects the principle of an individual being innocent until proven guilty. However, its purpose has been the subject of dispute by historians and courts alike. The historical context as well as defining the standard itself has proven to be difficult to determine. There are several theories on the intention behind the standard’s development as well as numerous interpretations of what the standard means. It is not the purpose of this article to form a conclusion on neither the historical development nor the definition of the standard. Instead, a discussion of a specific proposition of the standard’s development will be given as well as an examination of the several attempts made to define reasonable doubt.

A Possible Origin of Reasonable Doubt

There is evidence to suggest that the original intention of the reasonable doubt standard was not to protect the accused, but instead the jurors. The evidence provided for this claim lies with pre-modern Christian values concerning damnation of the soul. According to older Christian customs the conviction of an innocent man was considered a potential mortal sin. To combat this horrifying possibility the reasonable doubt jury charge allowed jurors to convict a defendant without gambling their own salvation, assuming that any doubt of guilt was not “reasonable.”

These medieval Christians were also concerned with the moral theology of judging and expressed concern for the soul of the judge presiding over a trial. This concern was especially stressed when there was the possibility of execution if the accused was found guilty and the judge contained any doubts about the facts presented. As the manifestation of an uncertain conscience, doubt demands to be obeyed. Early Christians seemed to agree with this sentiment and developed a standard referred to as the “safer way,” which stated when faced with doubt as a judge, the safer way is not to act at all. This dogma was upheld against not only judging, but also all acts concerning the individual conscience. So, when faced with any doubt, it was the duty of the judge to not judge at all. These directions were prevalent across all western Christendom spanning to the ends of Europe.

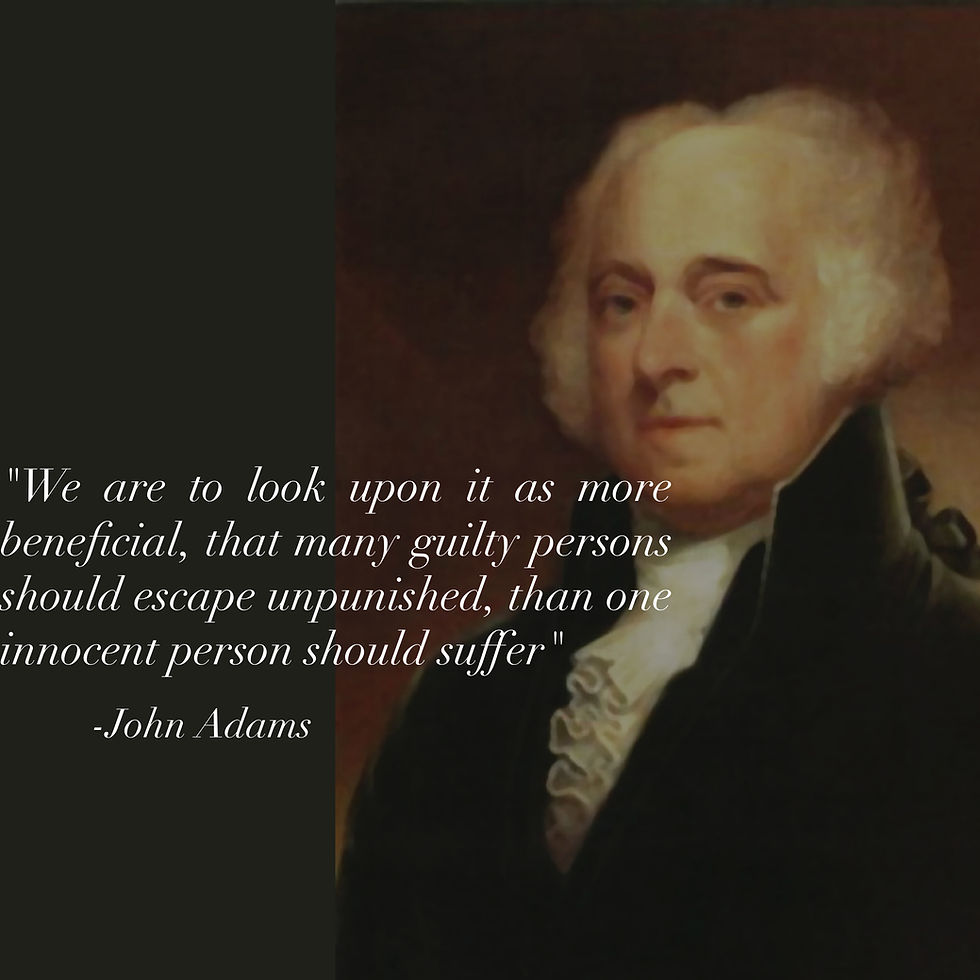

Whether the original intention of reasonable doubt was to protect those judging the accused from damnation has little significance on its intention today. In modern times the purpose of this standard is to protect the accused from wrongful conviction. However, it is important to discuss the truths behind convicting an innocent individual. Regardless of an individual's religion or beliefs, to convict another individual who is innocent is not only an indecency to humanity, but also objectively detrimental to one’s own conscience. Acknowledging this allows one to understand the magnitude of reasonable doubt’s significance when deciding the future of another human being’s life. Jurors are instructed to analyze the facts of a trial and in a clear conscience come to the verdict of guilty – if and only if – the evidence presented proves all elements of the offense with which the accused is charged beyond any reasonable doubt.

It is also important to discuss the premise of the “safer way,” doctrine in a modern context. This discussion is simple; the context remains the same because the fundamental principle of this standard is universal. Making a false statement to one’s own self or another morally corrupts the conscience. When a false statement is made regarding the fate of another individual the stakes are much higher. Not only is one’s own conscience corrupted but so is liberty itself. Therefore, when faced with doubt of any material fact that would condemn an individual to a guilty verdict, it is the duty of the juror or judge to find the individual not guilty. There is no dispute in this conclusion for the morality that constitutes the premise of the argument is objective.

Defining Reasonable Doubt

Although not explicitly included in the Constitution the standard of reasonable doubt has been a long-standing tradition in our judiciary system. It is the epitome of the values that this country was built upon; to protect the rights of the individual, to preserve the right of the people to hold the government accountable, and most importantly that all men are created equally. These principles have been woven through every piece of fabric that forms the union between these 50 states. However, these principles weren’t accepted into Constitutional law as a standard for the judiciary system until 1970. The Supreme Court read the routine standard of proof into our constitutional law in the case In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358. The Court determined that the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments guaranteed an individual the right to include that standard in a jury charge.

Following this decision, the Court has upheld the importance of this standard consistently without exception. In 1975 the Court made a further clarification in Mullaney v. Wilbur 421 U.S. 684, ruling that the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt every element necessary to constitute the offense charged. There have been several decisions since then that have allowed or excluded certain phrases in the jury instructions defining reasonable doubt. This alone is evidence enough to conclude that the phrase, “reasonable doubt,” is not easily defined; yet it is easily understood. Doubt is generally understood by the majority and is easily definable; but to determine what is considered reasonable isn’t as transparent. Certain judges instruct juries that a reasonable doubt is, “doubt based on reason.” Other understandings of this standard have juries convict if they feel the evidence has persuaded them to a moral certainty of the defendant’s guilt. Another explanation is the, “hesitate to act,” proposition where in Victor V. Nebraska the Supreme Court condoned the following, “Reasonable doubt is such a doubt as would cause a reasonable and prudent person, in one of the graver and more important transactions of life, to pause and hesitate before taking the represented facts as true and relying and acting thereon.” Although all similar, no explanation truly captures the meaning of reasonable doubt and allows for confusion as these definitions are not exactly rigid.

The ability to sum reasonable doubt into an all-encompassing phrase has eluded judges and lawyers for centuries. Nevertheless, this mystifying standard has contributed to the integrity of the judicial system since the infant years of our country. Regardless of the original purpose of the standard, today it serves to protect those that are accused of committing a crime. While there are difficulties in determining a uniform or even clarifying definition, this formula has proven to be the most effective safeguard of an individual’s rights and is one of the many reasons why this is not only the greatest judicial system, but also the greatest country in the world.

By Austin R. Vidal

Comments